After both the first and the second time I wrote about Lisa Montgomery, I heard from readers who said that in arguing against the upcoming execution of this severely mentally ill woman, who was routinely raped as a child and physically abused as a wife, I was somehow siding against her victim and their survivors.

“The family of Bobbie Jo Stinnett deserves closure,” one told me. “Many people go through the same problems” as Montgomery “and do not commit premeditated murder, especially one as horrible as that one.”

What the Stinnett family deserves is Bobbie Jo back at home, but no one can give them that. I hope it’s not true that “many people” are routinely raped by a stepfather and his equally drunk buddies. Or allowed to be gang-raped by a mother who charged men in exchange for letting them violate her daughter. This is not “My mom never encouraged me.” This is, “Once, to punish us, she killed the family dog and made us watch.”

After both the first and the second time I wrote about Lisa Montgomery, I heard from readers who said that in arguing against the upcoming execution of this severely mentally ill woman, who was routinely raped as a child and physically abused as a wife, I was somehow siding against her victim and their survivors.

“The family of Bobbie Jo Stinnett deserves closure,” one told me. “Many people go through the same problems” as Montgomery “and do not commit premeditated murder, especially one as horrible as that one.”

What the Stinnett family deserves is Bobbie Jo back at home, but no one can give them that. I hope it’s not true that “many people” are routinely raped by a stepfather and his equally drunk buddies. Or allowed to be gang-raped by a mother who charged men in exchange for letting them violate her daughter. This is not “My mom never encouraged me.” This is, “Once, to punish us, she killed the family dog and made us watch.”

Montgomery’s crime, cutting a full-term child from the womb of a 23-year-old pregnant woman in Skidmore, Missouri, in 2004, was without any question or qualification horrible.

But closure is a myth, and a cruel one. Some loved ones of homicide victims favor the death penalty, and others oppose it. Yet studies on whether those survivors later reported that their lives had been in any way improved by the execution of the killer of their family member found that the answer is no. In fact, those whose loved one’s murderer had instead been sentenced to life in prison reported better results in terms of healing and recovery.

Another reader wrote me to say that if we don’t kill brain-damaged, 52-year-old Montgomery, who is from Melvern, Kansas, then she might stage a jailbreak and kill again: “Once in a while prisoners do escape, sometimes with help. Remember when John Manard, a convicted murderer, escaped in a dog kennel with the help of a volunteer? That could happen with Lisa Montgomery and she could repeat her crime.”

The last time a death row inmate escaped anywhere in this country was in Texas in 1998. And how far did that guy get, you ask? Less than a mile. Guards shot 29-year-old Martin Gurule in the back as he climbed over two 10-foot fences topped by razor wire. His autopsy showed that he’d drowned later that same night in nearby Harmon Creek, where fishermen found his bloated body a week later.

Funny that reader should mention John Manard, though, because one of the few friends Lisa Montgomery has ever had in this world happens to be the woman who helped Manard escape.

Toby Dorr, known in the press as “the dog lady,” met Montgomery when both were in prison in Leavenworth. And what Dorr wants us to know is that Montgomery is someone who “just never had a chance.”

In prison, she was safe for the first time.

Toby Dorr, known in the press as “the dog lady,” met Montgomery when both were in prison in Leavenworth. And what Dorr wants us to know is that Montgomery is someone who “just never had a chance.”

Behind bars, Montgomery felt safe for the first time in her life, though she was also a pariah in custody because of what she’d done.

“There were no big surprises there,” Dorr said. “Our days were exactly the same, and I think that was good for her.”

She spent her time reading the Bible, quilting and tatting placemats and bookmarks. With the few, first friends she’d ever really had, Montgomery talked a little about her life — about the stepdad who repeatedly slammed her head into their concrete driveway and the step-brother, Carl Boman, her parents had moved into her room, then made her marry at age 18 after she became pregnant.

“Lisa didn’t even like him,” Dorr said, “and he abused her the whole time.” He was recently charged with sexually abusing a 14-year-old.

Still, Dorr said, Montgomery “believed in the good in the world, even though she never got to see much of it. She had finally found a peaceful place to exist.” And on medication for the first time, she herself was far more stable.

“Once they got her medications right, we were fine,” said her Leavenworth roommate for two years, Lisa Nordike, who lives in Independence, Missouri. “I even coaxed her out of the room to watch TV once in a while.” Before prison, “she said she had no female friends, or friends period, because Carl had isolated her, and she didn’t know how to make friends.”

Nordike hasn’t written to her old cellmate lately, though she prays for her every day. “Every time I try to pick up a pen …” she said, and started to cry. “What do you say?”

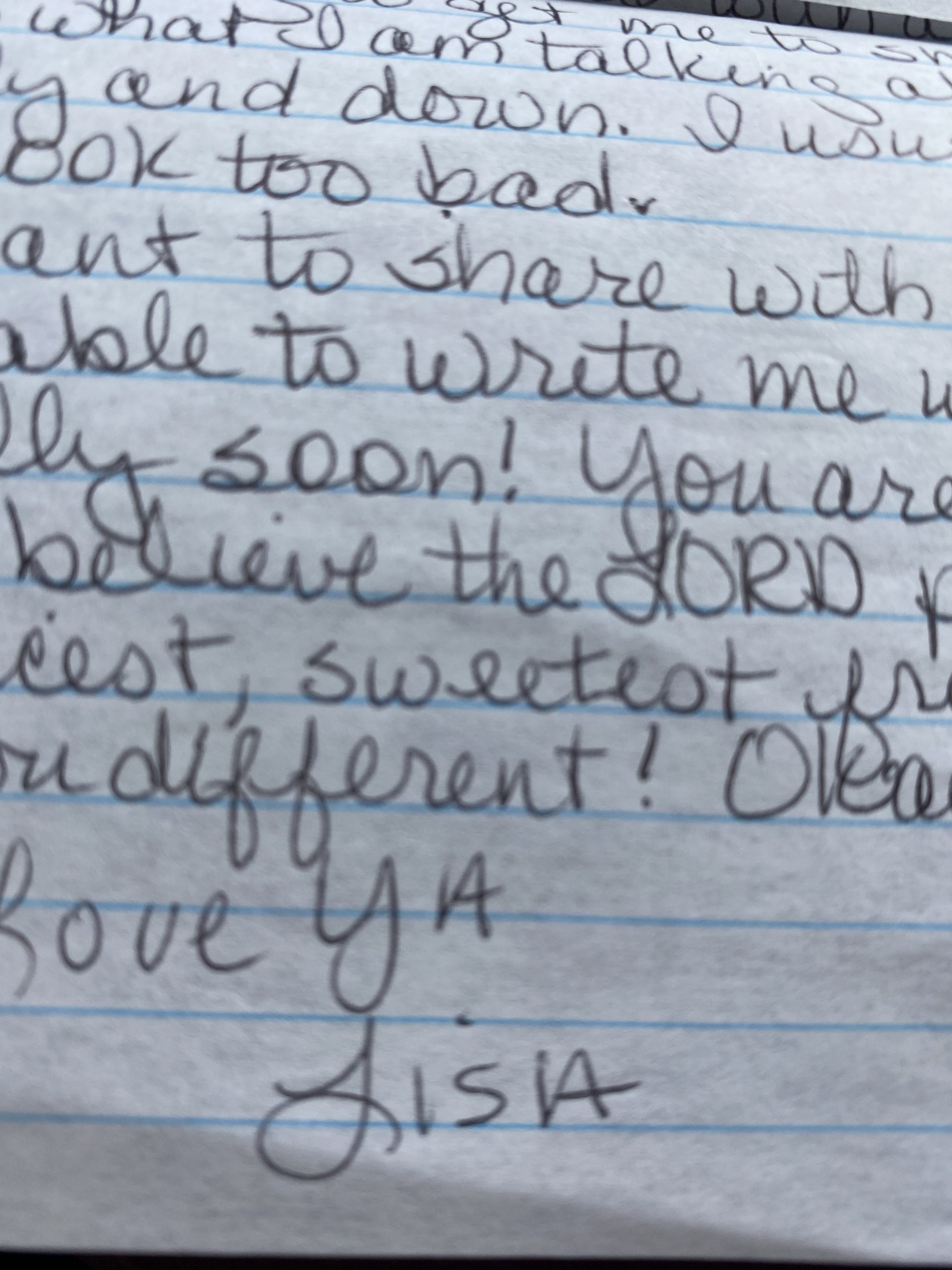

Dorr, though, recently got a letter from Montgomery, written in the black crayon that’s the only writing utensil she’s been allowed on suicide watch.

Montgomery said she was worried about how the other women in her unit would take her execution, and was trying “not to get lost inside my head.”

“Lisa is no threat to society in prison,” Dorr said. “The world does not become a better place, and her crime is not erased by killing her. She can make a contribution behind bars,” where she atones by giving away whatever she can. “If somebody needed Ramen noodles and Lisa had it, she would give it. I don’t see that anybody wins by killing Lisa Montgomery.”

Compounding one family’s trauma does not lessen another’s. Killing Montgomery won’t ease the Stinnetts’ pain, but will extend their suffering to Montgomery’s own four children, all of whom visit and correspond with her. Since she’s been in prison, she’s also connected with the biological father she hadn’t known before, who says he would have taken her if only he had known what was happening.

Plenty of others did know, though. In fact, her trafficking was so out in the open that Lisa’s mother would send the other kids out to play while she was being brutalized. When she told a cousin who was a deputy sheriff what was happening, he believed her but did nothing.

Even when she testified in court about the rapes, as part of her mother’s divorce case, the abuse was reported to the state, but no one ever followed up. Until she killed Bobbie Jo Stinnett, the government showed no interest whatsoever in Lisa Montgomery.

In reviving the federal death penalty last year, after a 17-year hiatus, Attorney General William Barr said we’d be executing “the worst criminals.” Instead, those put to death personify almost every argument against capital punishment.

The 10 federal prisoners executed in 2020 — the most in any single calendar year for more than a century — included a man with such late-stage Alzheimer’s that he didn’t know why he was being killed and two men who were teenagers at the time of their crimes. In our name, the government executed a Native American whose crime was committed on tribal lands, despite the fact that the Navajo Nation, which should have had sovereignty, opposes capital punishment. We killed a Black man convicted by an all-white jury. And a man with such a low IQ that he, too, should have been disqualified as too low-functioning to be put to death.

“The worst criminals,” as it turns out, is just another way to say the poorest and most impaired.

Unless President Donald Trump grants Lisa Montgomery the clemency that would allow her to spend the rest of her life in prison, she, too, will be executed. On Jan. 12, just days before the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden, who opposes the death penalty.

If Trump decides not to intervene, she will die as she lived. Without, as her friend Toby Dorr said, ever having had a chance.

“The family of Bobbie Jo Stinnett deserves closure,” one told me. “Many people go through the same problems” as Montgomery “and do not commit premeditated murder, especially one as horrible as that one.”

What the Stinnett family deserves is Bobbie Jo back at home, but no one can give them that. I hope it’s not true that “many people” are routinely raped by a stepfather and his equally drunk buddies. Or allowed to be gang-raped by a mother who charged men in exchange for letting them violate her daughter. This is not “My mom never encouraged me.” This is, “Once, to punish us, she killed the family dog and made us watch.”

After both the first and the second time I wrote about Lisa Montgomery, I heard from readers who said that in arguing against the upcoming execution of this severely mentally ill woman, who was routinely raped as a child and physically abused as a wife, I was somehow siding against her victim and their survivors.

“The family of Bobbie Jo Stinnett deserves closure,” one told me. “Many people go through the same problems” as Montgomery “and do not commit premeditated murder, especially one as horrible as that one.”

What the Stinnett family deserves is Bobbie Jo back at home, but no one can give them that. I hope it’s not true that “many people” are routinely raped by a stepfather and his equally drunk buddies. Or allowed to be gang-raped by a mother who charged men in exchange for letting them violate her daughter. This is not “My mom never encouraged me.” This is, “Once, to punish us, she killed the family dog and made us watch.”

Montgomery’s crime, cutting a full-term child from the womb of a 23-year-old pregnant woman in Skidmore, Missouri, in 2004, was without any question or qualification horrible.

But closure is a myth, and a cruel one. Some loved ones of homicide victims favor the death penalty, and others oppose it. Yet studies on whether those survivors later reported that their lives had been in any way improved by the execution of the killer of their family member found that the answer is no. In fact, those whose loved one’s murderer had instead been sentenced to life in prison reported better results in terms of healing and recovery.

Another reader wrote me to say that if we don’t kill brain-damaged, 52-year-old Montgomery, who is from Melvern, Kansas, then she might stage a jailbreak and kill again: “Once in a while prisoners do escape, sometimes with help. Remember when John Manard, a convicted murderer, escaped in a dog kennel with the help of a volunteer? That could happen with Lisa Montgomery and she could repeat her crime.”

The last time a death row inmate escaped anywhere in this country was in Texas in 1998. And how far did that guy get, you ask? Less than a mile. Guards shot 29-year-old Martin Gurule in the back as he climbed over two 10-foot fences topped by razor wire. His autopsy showed that he’d drowned later that same night in nearby Harmon Creek, where fishermen found his bloated body a week later.

Funny that reader should mention John Manard, though, because one of the few friends Lisa Montgomery has ever had in this world happens to be the woman who helped Manard escape.

Toby Dorr, known in the press as “the dog lady,” met Montgomery when both were in prison in Leavenworth. And what Dorr wants us to know is that Montgomery is someone who “just never had a chance.”

In prison, she was safe for the first time.

Toby Dorr, known in the press as “the dog lady,” met Montgomery when both were in prison in Leavenworth. And what Dorr wants us to know is that Montgomery is someone who “just never had a chance.”

Behind bars, Montgomery felt safe for the first time in her life, though she was also a pariah in custody because of what she’d done.

“There were no big surprises there,” Dorr said. “Our days were exactly the same, and I think that was good for her.”

She spent her time reading the Bible, quilting and tatting placemats and bookmarks. With the few, first friends she’d ever really had, Montgomery talked a little about her life — about the stepdad who repeatedly slammed her head into their concrete driveway and the step-brother, Carl Boman, her parents had moved into her room, then made her marry at age 18 after she became pregnant.

“Lisa didn’t even like him,” Dorr said, “and he abused her the whole time.” He was recently charged with sexually abusing a 14-year-old.

Still, Dorr said, Montgomery “believed in the good in the world, even though she never got to see much of it. She had finally found a peaceful place to exist.” And on medication for the first time, she herself was far more stable.

“Once they got her medications right, we were fine,” said her Leavenworth roommate for two years, Lisa Nordike, who lives in Independence, Missouri. “I even coaxed her out of the room to watch TV once in a while.” Before prison, “she said she had no female friends, or friends period, because Carl had isolated her, and she didn’t know how to make friends.”

Nordike hasn’t written to her old cellmate lately, though she prays for her every day. “Every time I try to pick up a pen …” she said, and started to cry. “What do you say?”

Dorr, though, recently got a letter from Montgomery, written in the black crayon that’s the only writing utensil she’s been allowed on suicide watch.

Montgomery said she was worried about how the other women in her unit would take her execution, and was trying “not to get lost inside my head.”

“Lisa is no threat to society in prison,” Dorr said. “The world does not become a better place, and her crime is not erased by killing her. She can make a contribution behind bars,” where she atones by giving away whatever she can. “If somebody needed Ramen noodles and Lisa had it, she would give it. I don’t see that anybody wins by killing Lisa Montgomery.”

Compounding one family’s trauma does not lessen another’s. Killing Montgomery won’t ease the Stinnetts’ pain, but will extend their suffering to Montgomery’s own four children, all of whom visit and correspond with her. Since she’s been in prison, she’s also connected with the biological father she hadn’t known before, who says he would have taken her if only he had known what was happening.

Plenty of others did know, though. In fact, her trafficking was so out in the open that Lisa’s mother would send the other kids out to play while she was being brutalized. When she told a cousin who was a deputy sheriff what was happening, he believed her but did nothing.

Even when she testified in court about the rapes, as part of her mother’s divorce case, the abuse was reported to the state, but no one ever followed up. Until she killed Bobbie Jo Stinnett, the government showed no interest whatsoever in Lisa Montgomery.

In reviving the federal death penalty last year, after a 17-year hiatus, Attorney General William Barr said we’d be executing “the worst criminals.” Instead, those put to death personify almost every argument against capital punishment.

The 10 federal prisoners executed in 2020 — the most in any single calendar year for more than a century — included a man with such late-stage Alzheimer’s that he didn’t know why he was being killed and two men who were teenagers at the time of their crimes. In our name, the government executed a Native American whose crime was committed on tribal lands, despite the fact that the Navajo Nation, which should have had sovereignty, opposes capital punishment. We killed a Black man convicted by an all-white jury. And a man with such a low IQ that he, too, should have been disqualified as too low-functioning to be put to death.

“The worst criminals,” as it turns out, is just another way to say the poorest and most impaired.

Unless President Donald Trump grants Lisa Montgomery the clemency that would allow her to spend the rest of her life in prison, she, too, will be executed. On Jan. 12, just days before the inauguration of President-elect Joe Biden, who opposes the death penalty.

If Trump decides not to intervene, she will die as she lived. Without, as her friend Toby Dorr said, ever having had a chance.

Read the article on Kansas City.com with this link:

https://www.kansascity.com/opinion/opn-columns-blogs/melinda-henneberger/article247993590.html